[ 14 ]

Presenting and Sharing Your Story

How Storytelling Helped Save the Day

Toward the end of 2010, we moved into a new office with Dare, and our experience planning team gained a new addition. Her name was Roz Thomas, and Roz’s background was in product design for, among others, what was then called Polly Pocket Group, a line of dolls and accessories. Roz was great at sketching up her thinking in ways that could easily be presented to the client.

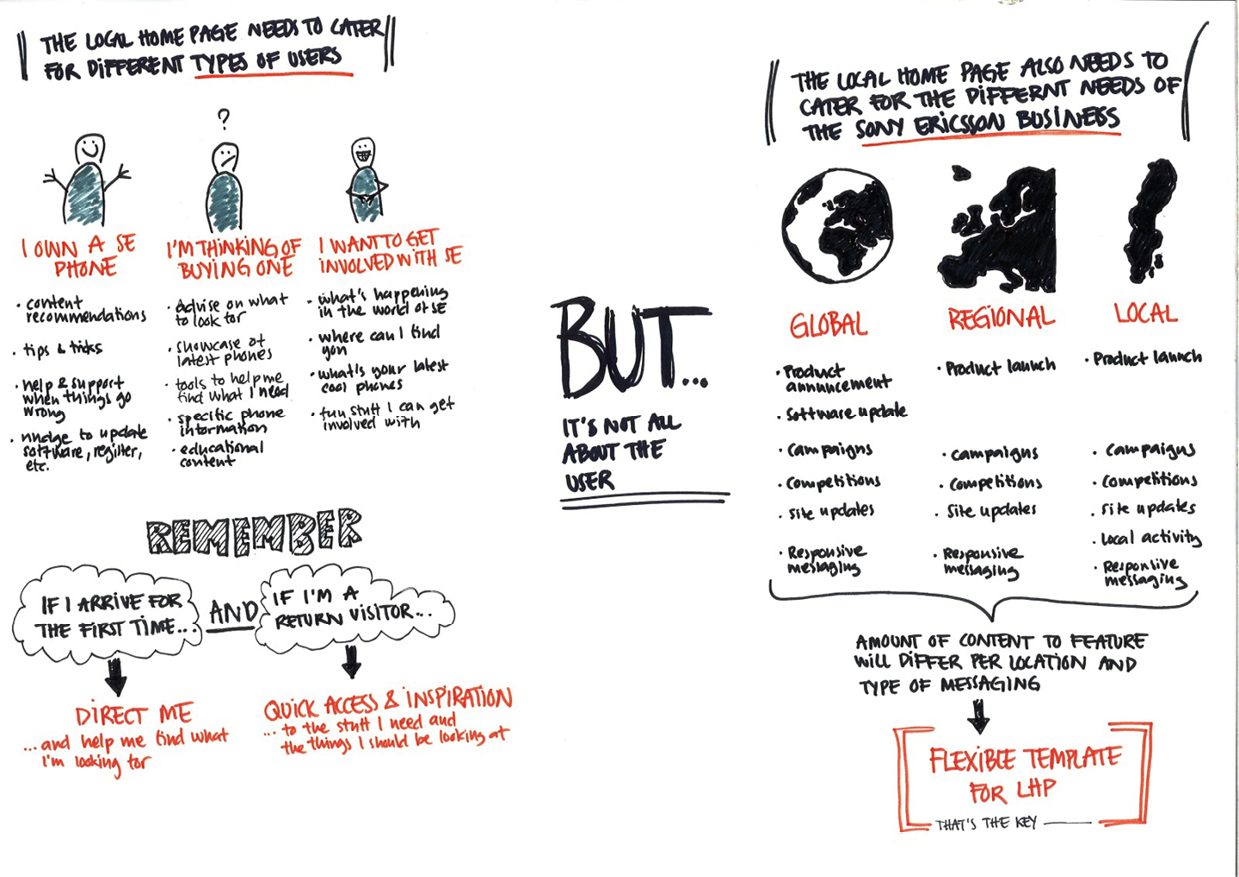

At the same time, I was working on a redesign of the Sony Mobile (previously Sony Ericsson) home page in preparation for a new phone campaign. We had received some initial feedback on the first version, and in my view, what our client was asking for didn’t meet the needs of the users or the business on a global or local market level. Inspired by Roz, I took to trying to sketch out my thinking.

Exactly how I ended up with what I did, I can’t recall, but somehow my scribbles, which were initially done for my own benefit to capture my thinking, turned into a comic-style document with the home page content depicted as superheroes. I used the illustrations to tell the story of why our original version of the home page was along the right lines. Our Sony Mobile team at Dare liked it so much that rather than talk the client through our feedback verbally, I ended up taking them through my comic-style sketches (Figure 14-1). They got a great response, and as far as I can recall, the client agreed with my pitch, and we went with our original recommendation.

Figure 14-1

My local home page approach walk-through

Though the outcome of that call might have been the same without the sketches, they helped bring to life the rationale behind our approach in a way that captured the client’s attention and allowed them to relate. Presentations, calls, and even conversations often fall on deaf ears because of the lack of emotional connection they evoke, which in turn is often a result of the way they’ve been presented or told. When something doesn’t grab our attention, those two thousand daydreams that all of us have each day start to make an appearance.1 As a result, we might end up saying “no” instead of “yes” (or receiving a no instead of a yes), all because we simply don’t connect and take in what the person presenting is saying. Similarly, the people on the receiving end don’t take in what we say when we’re presenting.

We had a really good relationship with the Sony Mobile team, and had it not been for that, I wouldn’t have been so comfortable presenting my superhero-style sketches to them. My presentation most certainly was a bit unusual, but sometimes that’s a good thing. As long as you take the client along on the journey, present the work in the right way, and set the right expectations, most types of deliverables and ways of presenting will work. Reaching your audience is just a matter of how you present them and what story you tell, and that it is the right story and the right focus for the audience.

The Role of Storytelling for Presenting Your Story

Throughout history and various professions, storytelling has been the way when it comes to presenting a tale. There is no separation between them. Telling someone something is storytelling.

All of us who are involved with product design—whether as a UX designer like myself or in a different role—are involved in creating the best possible experiences for our users. When it comes to using storytelling for presenting our work, the opportunity and value lies in how storytelling can be used to create a good experience for the people you present to and work with, be they team members, internal stakeholders and/or clients. Rather than simply present facts, rationale, feedback, or the work that we’ve done as is, storytelling enables us to turn the “tell,” as producer Peter Guber calls it, into an experience for our audience. Using storytelling might seem like overkill when it comes to work situations, but the more we can embrace that everything, including all aspects of work as far down as reading an email, is an experience, the better we can make those experiences.

In most workplaces, we’re expected to use logic and reasoning as a way to support and communicate our work. Yet storytelling (as covered in Chapter 1) is one of the most powerful ways to move people into action. Something happens in us when facts and messaging are embedded in a story. Stories help us remember details and events, and moves us emotionally. Reasoning and logic on its own can make the strongest of business cases fall flat, but embedding them in a story can move people emotionally.

In short, storytelling matters. It is such a powerful tool, in part because of what it enables us to accomplish. Next, we’ll look at four important ways we can use storytelling.

Using Storytelling as a Way to Achieve a Desired Outcome

One of the main things to remember when it comes to storytelling is that no matter what type of story you’re telling, or how you’re presenting it, in the end you’re trying to make something happen. Whether you’re offering a document, giving a presentation, or leading a meeting, there’s always a reason and a desired outcome.

Guber talks of purposeful stories, those that are told with a specific purpose in mind.2 The secret sauce behind his success has been in telling purposeful stories, he says, and it’s something anyone can do and see the results instantly.3 This is what the troubadours back in the Middle Ages did: they gauged the way their audience reacted and adapted their performances accordingly.

We see it today in journalists who present stories that evolve as they ask their questions. We see it in comedians who build up to a specific punchline, hoping that the audience will laugh, but then quickly adapt and try to save the situation if the joke falls flat. And we see it in great public speakers, who structure a speech for a desired outcome, but continuously gauge the audience reaction and adjust their performance based that.

Being clear on the call to action

With everything we do and everything we communicate at work, we want the person on the other side to do something. The power of storytelling lies first and foremost in telling purposeful stories that bring to life that call to action in a way that resonates with our audience. This applies to our work not only in terms of what it is, but also in how we present it, verbally and on paper. The visual and verbal presentation are critical aspects in making sure that our message resonates with our clients and internal team members. Besides, if we don’t know what CTA we want our audience to take, how can they take it?

Using Storytelling as a Way to Get Buy-in

One of the main overall desired outcomes we have for whatever we present is a wish for the team members, internal stakeholders, and clients to buy in to what we’re presenting. This desire for buy-in applies to concepts and ideas, proposed solutions, ways of working, and more. No matter how good your idea, approach, solution, or argument might be, if you can’t convince the team and/or the client, it will never see the light of day. This is true for getting buy-in for UX but also for the work that you do across every single step of the project process, stretching from ideation to post launch, from the first review to that final sign-off and post-launch follow-up. It’s one of the reasons that, as UX designers, product owners, and more, one of our key skills is to be great storytellers.

At times, we may have a tendency to think that our work or the proposition we’re presenting will sell itself. This is seldom the case. Being able to present the story related to your work is absolutely key for also getting buy-in. As Guber says, “If you can’t tell it, you can’t sell it.”

If you’re a writer and have spent the better part of a year or more on your story, but that story is never read, then it’s never told. It’s the same for startups, small business owners, musicians, etc.: it doesn’t matter what you create or how great it is if no one sees or hears it. This also applies to product design.

Other reasons buy-in is important

Besides selling our ideas and work, there are other key reasons buy-in is so important—the user’s experience, for example. Many organizations are struggling to change the status quo and to adapt to more agile and collaborative ways of working, as well as to fully grasp requirements for multidevice projects and digital overall. While conferences and the latest and most popular Medium articles might lead us to believe that most people “get it,” many organizations and many people don’t. Beyond making what we do and why it’s valuable understandable, and selling our ideas and work, there are other key reasons we should care and focus on getting buy-in. Getting buy-in can help do the following:

- Improve ways of working to ensure collaboration across disciplines and business units

- Break down silos in the organization

- Ensure a better use of budgets and everyone’s time

- Ensure everyone is on the same page

Understanding why there is a lack of buy-in

Working toward increased buy-in, whether for UX design or something else, should always start with understanding why that buy-in is lacking. More often than not, whatever the overarching reason might be, the underlying reason tends to come down to three issues, often in combination:

They don’t yet understand the value

Whoever is not bought in on, for example, UX design, doesn’t yet see or understand the value of UX, the role UX has, and how UX fits into the bigger picture and the project process.

They understand something else better

Whoever is bought in on, for example, UX design, comes from a different discipline and understands that and/or something else better (e.g., development), and as a result, prioritizes that in terms of allocating more budget to development or letting development lead the way.

The budget is focused elsewhere

Whoever influences the budget and schedule has prioritized them elsewhere, for one or both of the previous two reasons.

Who to get buy-in from

Having a better understanding of why there is a lack of buy-in is the first step in defining the story you need to tell in order to get the buy-in you need. The preceding three reasons provide a good starting point, though nuances exist. A key part of gaining buy-in is also understanding who you should focus on and the role they’ll play in ensuring your desired outcome. At a broad level, the “who” can be categorized as follows:

Internal team members

Your closest allies, whom you need to get on board

Clients and stakeholders

People who are in control of budgets and the “yes” or “no”

How to increase buy-in

With a good understanding of why there is a lack of buy-in, and whom to get the buy-in from, the next step is about identifying more about what will increase the chances for buy-in. To increase buy-in among internal team members, three main things need to happen:

Understand the story of the team and the individuals on that team

You need to understand the team’s backstory in addition to understanding where they are going. Depending on where the lack of buy-in occurs, you may need to look at the individual, the whole team, or a combination of both.

Identify what makes the other person or people the hero(s)

Each team member and each team will always have something that they particularly care about. If you’re met with resistance, try to understand why, and what will make the person or people in question shine.

Adapt your approach and your work

Based on what you’ve learned in the previous chapters, adjust the way you approach a subject, suggest an idea, or similar, so that it better fits with the specific team member or team.

Increasing buy-in with clients and internal stakeholders is similar but should have a clearer focus on the value put in context with what really matters to them. Though it’s not about playing games or bending over backward, we can often do little things that help the person in question do their job or look good in relation to someone they report to. Here are some steps you can take to increase buy-in among clients and stakeholders:

Identify the key clients and stakeholders

These will be the people you deal with both directly and indirectly. Understanding who has the decision-making power and controls the budget is the first step in increasing your chances of getting buy-in.

Identify what matters to them

This is about understanding what they respond best to. Using UX as an example again, some clients and internal stakeholders will simply prefer to focus on visual designs over UX deliverables, and that’s OK. If that is the case, make sure you place a bit more emphasis on the visual aspect of the UX deliverables.

Assess their current understanding of the subject

Your proposal should always take into consideration their prior knowledge of the topic. You don’t tell a story the same way to someone who is completely new to the subject as you do to someone who has a good understanding of it.

Tie the value of what you propose to what matters to them

This step is also about making them look good. If buy-in is about UX, tying the value could be about understanding how and where UX sits in the process for them and how it can be used to help and make them look good, not only with regard to what UX adds to the project, but also how each of the UX deliverables helps the client and their project get one step closer to a better end result.

Adapt how you present your work so it resonates with them

Some prefer a lot of details, and others prefer just a high-level summary. Hit the right balance to appeal to the person in question rather than give them a reason to immediately be put off.

Give them something tangible to share with the people they report to

The main client and stakeholder you most often deal with is not always the one in charge of the budget or the power to provide a final “yes” or “no.” For this reason, it’s important to provide your main stakeholders and clients with something they can pass up the chain of command that makes it easy for them to sell it.

Sometimes, however, when it comes to buy-in, you feel like you’ve reached a dead end. If the organization you’re working with has a very low level of UX maturity, you may need to partner with someone in a more influential position and get them to help tell the story of why and how UX should be involved in the organization.

This doesn’t necessarily need to be someone high up. You could team up with someone on the creative team, if the company is led by the big idea; a business analyst, if the company is led by the business; or engineering, if that’s what the company is currently most focused on, and so forth. The lone storyteller is often not the best way to go when there is a low level of maturity or buy-in. Instead, this is where you need an ensemble that can grow and grow until eventually the full organization has embraced it. Last but not least, if you want someone to get excited about what you’re proposing and the work that you’ve done, you have to make sure that you give them a reason to get excited, which is directly related to what we’ll cover next.

Using Storytelling as a Way to Inspire

In every great story, a bit of magic is involved as the storyteller makes us see things differently. Throughout history, great storytellers have had the ability to make this magic happen by capturing the imagination of their audience and transporting them into the world they’re describing. Whether inspiring people to action or simply capturing their attention and interest, all good storytellers spark that appetite and desire to hear more, and even to be around that person. In the workplace this type of great storyteller can take the form of a leader, manager, or colleague who always fills others with energy and a “Let’s do this” motivation whenever they speak. Or it can be the person who makes the complex seem simple, or makes what’s usually boring become interesting.

Guber says all good stories contain a promise of something to come. When that something is grounded in what makes the listener tick, the story becomes inspiring. It almost doesn’t matter what subject is being talked about or covered; if it’s told in a way that enables the listener to relate, it has the potential to inspire and to move people into action. History is filled with examples of great storytellers who had the ability to inspire others and get them to believe in what they believed in. Very few of us will have the same inspirational impact as these people, nor should we all strive to be great inspirational leaders and speakers. All of us can do little things to help our workplaces and work environments be more inspiring.

The pull of possibility

Storytelling plays an important role in inspiring and motivating others. Chapter 2 introduced Nancy Duarte and her analysis of great talks. Duarte looks at speeches by Martin Luther King Jr. and Steve Jobs in detail and visualizes how they move from What Is to the New Bliss in various ways.4

In Steve Jobs’s iPhone launch speech, Duarte color-coded where he talked, switched to video, and then demo. She also overlaid audience reactions at various points as well as how Jobs himself deliberately reacted to reflect what he wanted the audience to feel. He marvelled saying things such as “Isn’t this awesome,”“Isn’t this beautiful,” and by doing so, Duarte says, he compelled them to feel a certain way.

Martin Luther King Jr., on the other hand, reached into his listeners’ hearts by using metaphors as well as by referencing scriptures and songs that resonated with the audience. Through the use of repetition and comparing what currently is to what could be, King connected with people.

Both King and Jobs have iconic lines in their speeches. For Martin Luther King Jr., it was “I have a dream…,” which he repeated over and over. For Steve Jobs, it was “Every once in a while a revolutionary product comes along and changes everything.” Each one deals with the promise of what’s to come, the thing that connects with us emotionally. They are another take on “Once upon a time” or “In a galaxy far, far away,” and however we start or end our stories, when told right, we know that something good is to come.

By structuring our story and its presentation to incorporate the pull of possibility, we increase our chances of creating mental images for the audience of what could be. Just as a comedian builds up to a main joke, we can use narrative structure to identify when and how to build up to the main part and how best to tell the story from there on to make sure we get the desired action. Sometimes, however, something more tangible is needed as well, in order to reach the desired outcome of attaining buy-in or inspiring people—and that’s data.

Identifying and Telling the Right Story Behind Data

Steven Levitt, author of Freakonomics and SuperFreakonomics, believes that “data is one of the most powerful mechanisms for telling stories.” In fact, that’s what he does—he takes huge amounts of data and tries to get it to tell a story, from the one about why so many drug dealers live with their mothers, to the story of how teachers cheat on behalf of their students on tests. His stories from data are what made him famous and eventually won him the John Bates Clark Medal, one of the most prestigious economic science awards.5

Economist Dan Ariely says, “Big data is like teenage sex—everybody talks about it, nobody really knows how to do it, everyone thinks everyone else is doing it, so everyone claims they are doing it.” Levitt argues that when you look back historically, it’s traditionally been business people who have been the experts when it comes to data. It’s been their job to ensure that people got what they wanted and knew the answer. But with the development in big data, the goal is no longer to know the answer, but instead how to leverage the data effectively. Levitt continues:

The future of business lies with the companies that understand how to use the data to inform their strategies and personalize their services.6

Many organizations sit on a ton of data, but as the quote implies, very few know how to get it, use it, or apply it. No matter what we’re using data for, whether it’s for part of an interface, findings in a report, or a presentation, the data always has a story to tell. The tricky part is that data can tell us anything, or absolutely nothing, if we don’t know how to interpret it. Understanding and working with big data is a discipline in and of itself—one that Harvard Business Review called “the sexiest job of the century” in 2012.7

The key to untapping the value that lies in big data is, according to Levitt, to break down organizational silos and encourage collaboration across departments and teams. The catalyst for this to happen often lies in a realization of the benefit that comes from doing so. Just as all UX designers don’t have to be—or should be—expert coders, neither should we all be data scientists or experts, but it helps to have an understanding of how we can use data in the design process, as part of the design, as well as to both present and evaluate what we’ve done. But we need to know what to use and how to use it, or we risk basing decisions on the wrong information.

Understanding the story behind data and what data to use

Over the last few years in particular, data-driven design has become such a hot topic that many jump on board without fully understanding the context. Many of us are familiar with Google’s 41 shades of blue: the company analyzed the range between two blues used on its home page and the Gmail page, respectively, to find the one that was most effective so it could be standardized across the system. Some companies have jumped to running similar tests. In one horror story, a company ran tests every single day, and based on the outcome, changed things on the fly, daily.

The risk of becoming this data driven is that you look at the data in isolation and mistake it for telling you a truth, which in fact is a lie. As our interactions and behavior online are becoming more complex and influenced by a growing list of factors, including external nondigital ones, there’s a real danger in looking at a single metric and basing decisions on that. These single metrics are often called vanity metrics because they don’t actually tell us anything or provide a false picture based on a lack of context.

When we incorporate data into the work we do, we might be working with quantitative or qualitative data:

Quantitative data

This data focuses on a breadth of information to enable us to find patterns and common ground. It’s numerical data that is usually focused on answering “who,” “what,” “when,” or “where.” Surveys and analytics are quantitative methods.

Qualitative data

This nonnumerical data is more focused on the “why” or “how.” Rather than aiming to get as many responses as possible, we use this data to go beyond just the answer to understand the reason. Common qualitative methods are observations and interviews.

Many vanity metrics are based on quantitative data. Page views and average session duration are two examples of metrics that are often used without context; a higher number is commonly assumed to be a good thing. It can be, but it can also be a bad thing, all depending on the context. As noted in Chapter 5, we need to take into account a growing list of factors in the experiences that we design. This doesn’t apply just to the way we consider and incorporate them, but also to the way we measure them.

As UX designers, understanding data and being able to work with it are increasingly important skills. We want to be able to use analytics to inform (or not inform) design decisions, set KPIs, and present insights from data in a compelling and value-adding way. We should also understand what data is available from users, how we can use it and how we shouldn’t, and whether we’re even allowed to legally use it.

Using metrics and KPIs to help tell your story

When we work through, define, and design websites and apps, there’s always something that we want a user to do. As I noted earlier in this chapter, if we don’t measure it, we won’t know if what we set out to do was a success or not.

KPIs have commonly been something that marketing, strategy, or the suits have dealt with. Far too often, the UX and design team aren’t involved in defining what the KPIs should be, or whether they indeed were met.

Your KPIs should, however, be closely related to the goal of the experience. This is where having defined objectives for your pages and views and experience goals really helps. Thinking through what your KPI would be for each experience goal, as well as the overarching one(s), and for your pages and views, is a great way to be specific about how you’ll know whether something is successful. As with all things, using KPIs doesn’t end by just setting them, but should be followed up on to see if, in fact, the KPIs were met.

Visualizing data

Many of us have sat through a presentation with poorly designed slides showing chart after chart, and as soon as whoever is talking through and explaining them has moved on, we’ve forgotten all about the details and can’t for the life of us figure out the meaning of a slide by simply looking at it. Visualizing data might bring to mind various kinds of information dashboards presenting a wealth of data and, hopefully, some meaning around it. While information dashboards can certainly help reduce the dependency on short-term memory by displaying (all) relevant data in one place, the need for and value of visualizing data goes well beyond information dashboards.8

Not too long ago, being able to visualize data was a “nice to have.” Now it’s close to a “must have,” particularly the higher up the career ladder you climb. However, basic visual communication skills is a must-have skill across at all stages of your career. As Aristotle wrote, the way we tell a story has a profound impact on the human experience, and in his seven golden rules of good storytelling, decor plays an important role. Just as design has become a competitive advantage, being able to visualize data and present it is something that will set you apart from,―or back from,―your competition, whether that’s a colleague in the same company, a candidate somewhere else, or a competing website or app.

No matter what you’re presenting, the ability to visualize data will help break information into parts that are easier to digest and understand. All data has a story to tell, but we need to get it out in order to be able to tell it. As the data we create and subsequently have access to via, or for, the websites and apps we create, the importance of being able to break it down and present it in a meaningful way for its purpose and audience is critical.

Visualizing data is important because it helps us to do the following:

- Reduce dependency on short-term memory

- Reduce cognitive overload

- Guide the eye of the reader

- Provide information for decision making

What Traditional Storytelling Can Teach Us About Presenting Your Story

Many of the methods and tools covered in this book can help us with the presentation part of our work. As I’ve said previously, everything is an experience, and though you can never guarantee that someone will experience something in a particular way, you can design the experience to be as optimal as possible. This section explains five steps to using storytelling for presenting your story.

Identifying the “Who” and “Why” of Your Story

All good stories are told with someone specific in mind. In traditional storytelling, that someone may be part of a large and broad audience with diverse needs and tastes, but the plot and the characters for one reason or another resonate with them (Figure 14-2). When presenting our story at work, we might still have a broad-ish audience in mind—the larger company if it’s about an approach to work, or the direct team or client if it’s about a proposed solution, for example. However, the more we understand about the specific “who” of those we present our story to, the higher the possibility that we’re able to tell it in such a way that it resonates and we achieve our desired outcome.

Figure 14-2

Identifying the “who” and the “why” of your story

The desired outcome is closely related to the “why” of your story. For most of the work we do and most of the presentations we put together, we have a reason for doing so. But often it’s just a high-level “why” that we’re aware of and able to articulate. Many deliverables and presentations leave their audience second-guessing about what it is they are looking at, or what the main takeaway should be, rather than the presenter being explicit enough to prevent confusion.

As we’ve covered previously, characters should ideally come before plot in relation to product design, as it’s all about the users in the end (without users, there will be no product). However, most design includes the idea of a plot; that is, a “what” that product should be, before detailed work begins on who the product is for.

Similarly, in presenting our work, there is often a “why” that leads to the “who.” Most people will start with a “why” (e.g., to increase sales) or a “what”(e.g., a redesign), and though the “who” is ever present, the details about the “who” often follow as an extension of “why” and “what,” and that is absolutely fine. The main thing is that all are clear.

According to Aristotle, plot and character are on par with each other, and that’s the case with the “why” and the “who” of the story you’re telling too. For example, your team may be working on a client presentation (the “who” being the client) to sell a concept or idea (the “why”).

Just as we in product design need to be specific and clear on who our audience is, what their needs are, and why our product and service is for them, when it comes to presenting our story, it’s important to do similar up-front work identifying our audience. It’s not something that has to take more than 15 minutes, but the impact of going through a simple “who” and “why” can pay off immediately.

In summary, the “who” and the “why” of what you’re presenting can be defined as follows:

Who

Your primary and secondary audience

Why

Closely related to the “who” of what you’re presenting and is about the desired outcome

How to go about it

Principles related to personas, empathy maps, and character maps, as covered in Chapter 6, are applicable as ways to work through the “who” and the “why.”

A first step, however, should always be to more precisely define the “who,” as it’s only then that you can really focus on what the specific people who will be subject to your presentation will care about. Leaving it as presentation (what) to the client (who) to sell our latest work (why) is very nonspecific and doesn’t take important details into account. In most instances, you’ll be presenting to not only your main client contact, but also their superiors and often the ultimate decision makers and budget holders who the presentation will be passed on to.

Many of the methods and exercises used in this book can be used to also help identify the “who” and the “why” of the story you’re telling. Chapter 6 presented a common list of characters in product design. This forms a useful basis for working through which characters apply to the product or service you design. Similarly, a more general list of the “who”s when it comes to presenting your story forms a useful starting point for defining the specifics in your situation.

Just as the characters in product design will differ based on your company and your role, the “who” will differ too. There are, however, various stakeholder analysis techniques and maps that can be used no matter the project. One of those techniques is the “Power/Interest Grid for Stakeholder Prioritization” which identifies which stakeholders need to kept “satisfied” versus just “informed.” Another one is stakeholder maps, which goes into more detail about the needs of the respective stakeholder. The latter is similar to a user persona.

Defining Your Story

The next step after having defined the “who” and the “why” is to plan out and start defining your story. Many of the methods and exercises we’ve covered in this book that relate to defining your product or service experience also apply to presenting your story. For instance, both the two-page synopsis method and the index card method as covered in Chapter 5, work well for working through the narrative structure.

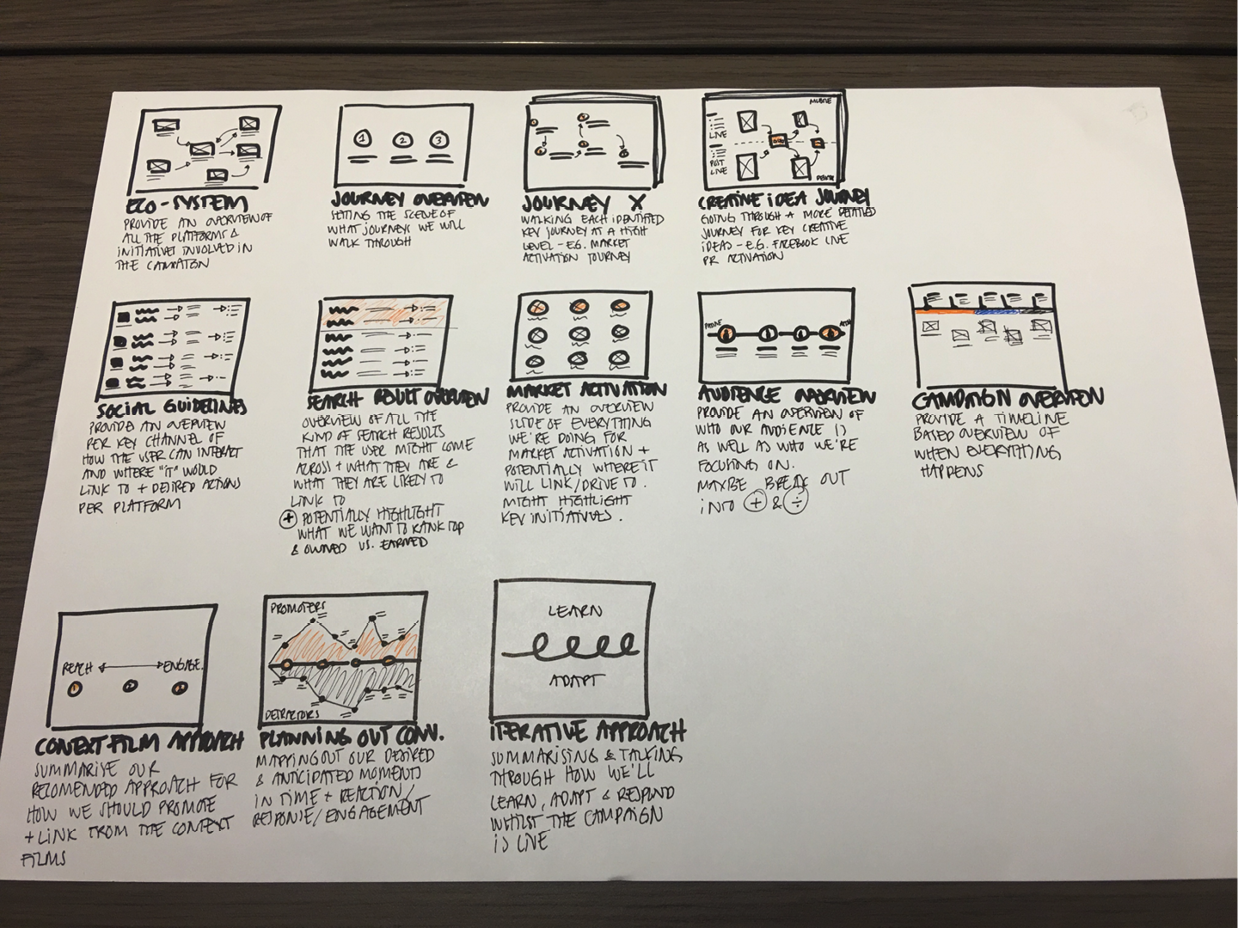

Whether you’re putting together an actual presentation or simply figuring out what you need to define and work through to best meet the brief, I advise the UX teams, strategists, and business people that I mentor and work with to quickly sketch up an outline before getting stuck (Figure 14-3). With a simple framework in place and a clearly defined narrative, plot points, and that last act when everything comes together, you’re ensuring that you’re clear about what steps you need to take. This outline also becomes a valuable tool and something physical to take to the rest of the team to talk through. If done properly—and this often doesn’t take more than an hour—you’ll clearly be able to talk through “This is what I recommend that we’d do and here is why.”

Figure 14-3

Defining your story

Over the last few years, this has become my default way of approaching projects, particularly when I’m working with new agencies that I’m not yet familiar with in terms of their ways of working or how much knowledge they have of UX and more strategic experience planning pieces. This process is also incredibly valuable for more junior UX teams who are developing their strategic and presentation skills, as well as any UX team working on getting more buy-in for UX deliverables in an organization. It’s a simple way of storyboarding what you need to cover and how it all fits together. Usually, it takes a couple of sketches before I get it right, but that’s part of the process and what makes it so incredibly valuable. Thinking you need to do something to only realize when you have the full story in front of you that you don’t, potentially saves a lot of time. Less is usually more, and if you can say something in one diagram/slide, that’s generally better than two, three, four, or five slides.

This process is similar to sketching out pages or app views and writing down “The purpose of this page/view is to…” as we talked about in Chapter 13. Sometimes people can be a little resistant to this process, as they just want to get the work done and jump straight into the details. However, taking a step back to first get that full picture—whether for a presentation structure, the kinds of deliverables you need to do, or your pages and views—usually saves a lot of time in the long run, plus makes the information much more to the point. And that’s usually a good thing, since no matter how formidable our presentation or deliverables might be, if things can be presented in less time and fewer pages or slides, that’s a plus. We can hold our attention for only so long, and there are generally other things to do afterward. After all, even the best stories must come to an end.

How to go about it

Thinking of the metaphor of a presentation, start by working through what slides you need and sketch out each one. Together with the “blank slide,” write down the purpose in a few words (e.g., “Persona overview,” “Key templates”). If you want to take the process one step further, add the main points each slide needs to make in order to address and answer the statements. The output might look something like Figure 14-4.

Figure 14-4

Sketched-out slides

The Verbal Aspect of Your Story

The verbal aspect of your story is very closely related to the written aspect of your story. But there’s a performance element added to it (Figure 14-7). When you’re working with just the written word, you don’t have the opportunity to conduct the auditory aspect of how that story is told.

Back in the old days, one of the reasons troubadours were so successful and being a storyteller was regarded as a great profession was their ability to adapt to as well as captivate their audience. They paused at planned and intentional times to ensure certain details came across with impact. It was a well-used technique back then, and it is a well-used technique today. How the storyteller or performer approaches it ties back to the overall narrative structure of the performance.

Figure 14-5

The verbal aspect of your story

We see this in great speakers, be they motivational speakers like Tony Robbins, speakers at conferences, or internal team members who present something in front of the company or client. What all of these have in common is that they read their audience. By looking at the audience’s response, or lack thereof, the speaker adapts accordingly. They pay attention and invite questions to be asked and create both a safe and inspiring environment. With the right verbal presentation style, the most seemingly uninteresting topics can be made interesting. Whether or not you achieve this comes down to how you tell that story and how you engage the audience.

How to go about it

Delivering your presentation starts with knowing the story and what you’d like your audience response to be at each key point. One way of working through this is to draw on the material covered in Chapter 9. Try to map out visually what you’d like the emotional response to each slide to be in your presentation.

You can do this in various ways; for example, by writing an “L” for low, “M” for medium, or “H” for high in the top-right corner of each slide, as sketched out as part of the following exercise. Or you could simply draw lines between each slide, connecting them at the bottom if the emotional response is lower, the middle if it’s raised somewhat, or at the top if it’s a higher-engagement moment.

With a clearer picture of the presentation as a whole, and the slides”that make it up, it’s easier to start thinking about the verbal presentation. You can identify what to say on each slide and what level of detail you want to go into. For the latter, it’s useful to come back to the “who” and “why” so you get the balance.

The Visual Aspect of Your Story

In traditional storytelling, the visual aspect (Figure 14-6) has often played an important role. Chapter 1 described how the Australian Aborigines used cave paintings both as a way to remember the story they were about to tell, and as a way to bring it to life.

When it comes to the work that we do in relation to product design, we sometimes forget about the importance of the visual aspect. Numerous companies don’t overlook its importance, and ensure that visual or graphic designers create the presentations that are given. And, of course, there are companies that do forget, and it shows. The visual aspect, however, doesn’t just apply to presentations in relation to product design. It applies to every output and deliverable, from emails and project plans to strategic, UX-related, and technical documentations, and everything in between. With everything we do, we tell a story, and the way we tell that story affects the way it’s experienced. Whether we want to or not, the way we present something “on paper” impacts the way the intended, or unintended, audience reads and understands the subject, or how they don’t understand it.

Figure 14-6

The visual aspect of your story

Dribble and Pinterest are filled with stunning-looking deliverables. The real world does, at times, look a little different. Some might argue that the purpose of UX deliverables is not to look good—and sure, that’s not the primary purpose—but it’s not an excuse for not caring about the visual presentation. Our job as UX designers is to bring clarity to experiences, to work with the information hierarchy, and make things easy to use. Yet, many UX designers forget to apply these same principles to the work they produce, sometimes to the point where it’s not even clear what you’re looking at.

To some extent, the way what you present looks says something about how much love and attention you’re giving the project. You don’t have to have great visual design skills in order to create nice-looking deliverables, or write clear emails and reports, for that matter. You just have to be clear about the story you’re trying to get across, what the desired action is, and apply simple information hierarchy principles to support that. In addition, you need to keep usability, readability, and relevance for your audience in mind.

How to go about it

With a clear “who” and “why,” as well as an understanding of the verbal aspect of the story you’re telling, the next step is about bringing that story to life. A key thing to remember here is the purpose of the presentation or the deliverable and how it’s going to be used. As a general rule of thumb, you should have less text in presentations that are given mainly in person or via video/ phone meeting than if they are simply sent around. In the latter case, more explanatory text is needed.

It’s also useful to go back to the desired emotional response and put more visual emphasis on the high moments, where you want to inspire or really draw your audience in. However, depending on who your audience is, perhaps a high moment is one with a lot of data and detail. It all depends on your “who” and “why.”

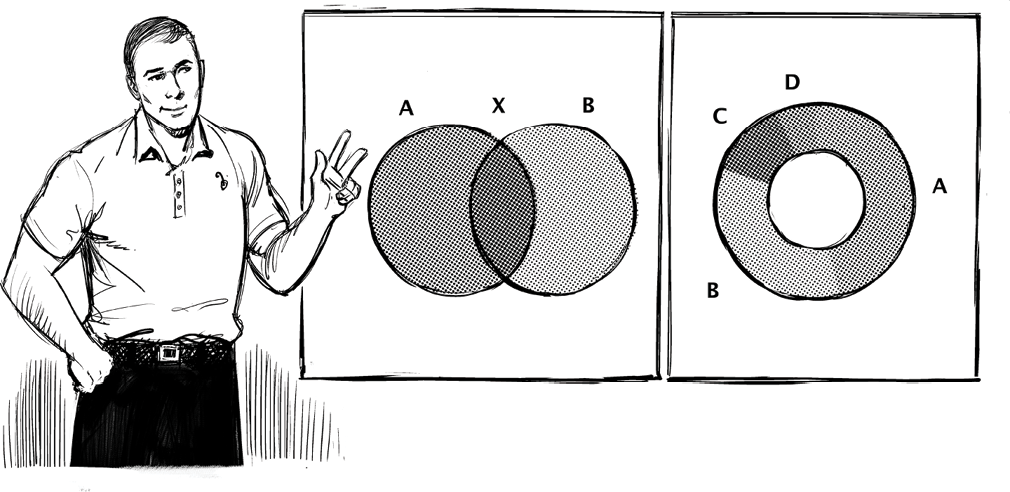

Adapting How You Present Your Story

As we talked about in Chapter 2, Aristotle was the first one to point out that the way we tell a story influences the raw human experience of that story. Just as we aim to adapt and tailor the experience we provide our users based on who they are and where they are in their journey, we ought to adapt what we present and how we present it to the client or stakeholder in question based on what they know, what they care about, and where we are in the project journey (Figure 14-7). This applies to both their understanding of UX and the level of detail we go into.

Figure 14-7

Adapting how you present your story

When you think about it, this adaptation is similar to the way we tell stories in our day-to-day lives. You won’t talk to a five-year-old child about your day at work in the same way you’d talk a grown-up, or tell a story with the same detail to someone who hears it for the first time and someone who’s heard it a hundred times before. Equally, if a client has extensive experience with or knowledge of UX and UX deliverables, there is no need to go through what a sitemap is, what the purpose of wireframes are and aren’t, etc., but the background becomes critical if they don’t.

How we tell our story in the best way has a lot to do with where we place the emphasis, and this in turn should link back to the “who” and the “why.” It’s also influenced by a number of other factors, such as these:

- What’s the key thing we want to get across?

- What do we need to get input or feedback on?

- How much do they know already?

- What does the person in question care about?

The last question is very much about what makes the person we’re presenting to “click” or not “click.” Some internal stakeholders and clients want all the details, whereas others want just the key points. Which side of the spectrum they are on makes a crucial difference to how we present our work on paper and verbally, what we include, and how we structure it. Failing to get this right often leads to unengaged clients, or clients who don’t give you the feedback that you need.

If the aim is to get buy-in, there are some additional things to consider:

- What is their current understanding of, for example, what UX?

- What is their current understanding of, for example, where UX sits in the organization and process?

- What is their current understanding of, for example, the value of UX?

- What is their current understanding of, for example, how UX could help projects and the organization?

Summary

As we’ve covered throughout this book, storytelling is an integral part of the design process—a practical tool to help narrate, inform, structure, prioritize, and plan out what you work on and how to bring it to life as an experience that fits into the user’s own story. But just like storytelling in the good old times was used to educate, entertain, pass on values, and move people into action, the role of storytelling in the workplace serves the same purpose:―to unite people around common visions and goals and to get buy-in for projects, ideas, and approaches to work, as well as win new clients and directives, and of course, as a way to better present our work.

No matter what level you’re at in your career or how much of your day-to-day work involves presenting in various ways, being a storyteller is part of all of our jobs. Although we won’t all become experts, we can all definitely master storytelling to some degree and see the direct benefits as soon as we put it into practice.

Presenting your story requires being both intentional and purposeful with the story you’re telling, and knowing why and how to tell it. It’s about acknowledging that not everyone will respond to the same thing, but that colleagues and clients are all different, just like the users of the products and services we design. Being a storyteller is a skill that has to do with listening and research. It’s about understanding nuances and being able to adapt and respond right then and there to how your audience is reacting. And it’s about having confidence in yourself and the material or subject you’re talking through. More than anything, it’s about creating a good experience for your audience, and although a story told is not necessarily a good one, a story told well has the power to change people’s minds and move them into action. And that is, after all, what we’re almost always after in work-related situations.

1 Jonathan Gottschall, “The Science of Storytelling,” Fast Company, October 16, 2013, https://oreil.ly/dekVH.

2 Mike Hofman, “Peter Guber on the Power of Effective Communicators,” Inc., March 1, 2011, https://oreil.ly/jxvOC.

3 Arianna Huffington, “Why Peter Guber’s Book Tell to Win Is a Game Changer,” HuffPost, March 1, 2011, https://oreil.ly/nklqy.

4 Nancy Duarte, “The Secret Structure of Great Talks,” TEDxEast Video, November 2011, https://oreil.ly/XSSWO.

5 Anne Cassidy, “Economist Steven Levitt On Why Data Needs Stories,” Fast Company, June 18, 2013, https://oreil.ly/IvUlm.

6 Jessica Davies, “Authenticity is key to multiplatform storytelling, says economist Steven Levitt,” The Drum, May 29, 2013, https://oreil.ly/Z4udi.

7 Thomas H. Davenport and D.J. Patil, “Data Scientist: The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century,” Harvard Business Review, October 2012, https://oreil.ly/MXzem.

8 Shilpi Choudhury, “The Psychology Behind Information Dashboards,” UX Magazine, December 4, 2013, https://oreil.ly/pDhON.

Find answers on the fly, or master something new. Subscribe today. See pricing options.